“Alphawave IP’s declaration of its intention to float on the London Stock Exchange comes at a particularly interesting time for many reasons,” says AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould. “The global silicon chip industry is booming, British investors are on the look-out for hot technology stocks and the UK Government’s examination of NVIDIA’s planned purchase of ARM – a company which has the same operating model as Alphawave IP – highlights the importance of the semiconductor industry to the economy, both here in Britain and worldwide.

“Silicon chips – or semiconductors - are everywhere we look, from our mobile devices, to our computers, cars, washing machines and fridges and new developments within the industry, as chips get physically smaller even as they offer more processing power, will play a vital role in the advancement of 5G mobile technology, artificial intelligence, electric and autonomous vehicles, the Internet of Things (IoT), data networking and cloud storage.

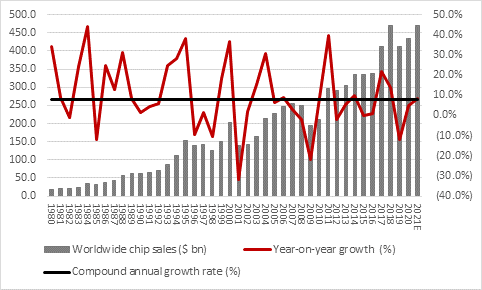

“Global chip sales rose 5% in 2020, despite the pandemic and the subsequent global downturn, reaching a new high of around $430 billion. Further economic growth, increased silicon content per unit in key end markets like autos, mobile devices and data servers, and supply tightness are expected to fuel global sales growth of around 8% in 2021, bang in line with the industry’s long-term compound annual growth rate.

Source: WSTS, SIA, Statista, consensus analysts’ forecasts

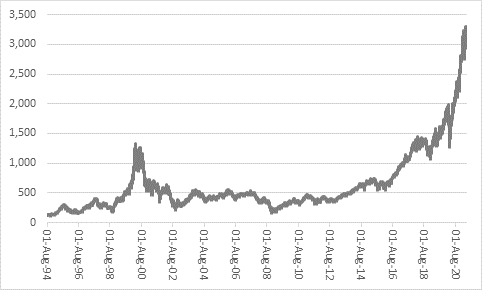

“This strong performance despite the testing economic backdrop has not escaped the attentions of investors. A key benchmark, the Philadelphia Semiconductor index, known as the SOX, trades only a fraction below its all-time high, set earlier this month. The US-based SOX, launched in 1994, contains 30 global chip and chipmaking equipment stocks. Most of them are American, although some hail from Asia and one – ASML – from Europe. None come from the UK.

Source: Refinitiv data

“This could all hope to stoke interest in the Alphawave IP flotation, especially as the UK market still lacks the exposure to fast-growing industries that many investors crave, although stock pickers will still look to apply the four classic tests which they should use to assess any firm, new or well-established, according to Warren Buffett’s long-time business partner Charlie Munger:

• Do we understand the business? UK investors will be familiar with Alphawave IP’s operating model as it is the same as that of ARM, a firm whose phenomenally successful run on the London Stock Exchange after its 1998 flotation came to end when Softbank bid £23 billion to acquire the Cambridge-based firm in 2016. Like ARM, Alphawave is a Semi IP company, which neither makes nor sells silicon chips but instead licenses out architectures which other chipmakers use as the basis for their own products, to save themselves time and money during the product development process. Like ARM, Alphawave will also bank a royalty every time a device is sold which features chips based upon on of its designs. [See Appendix below for an explanation of the different types of semiconductor – or silicon chip – companies]

• Does the business have intrinsic value – a competitive position that it can defend? Semi IP companies tend to have sticky customers, as it can be major wrench to switch design architectures, and new products can generate a fresh round of license fees as well as further royalties. However, customers can switch – as Imagination Technologies found out to its cost when Apple moved on – so ongoing investment in research and development is vital.

• Does management have integrity and are its interests aligned with those of investors? After the brouhaha generated by Deliveroo’s share structure, investors will be looking carefully at who owns Alphawave IP’s shares, management’s track record and the composition of the board, to ensure the board offers the right mix of skills and experience to help the firm transition from being a private to a public company.

• Do the shares come at a fair valuation? The price paid for a share – and the valuation paid to access a company’s profit and cash flow streams – is the ultimate arbiter of investment return. Whether the proposed Alphawave IP IPO flies or flops will depend on the price investors are initially asked to pay and then whether the company can live up to – or exceed - the expectations set by its price tag.”

APPENDIX: Different types of semiconductor companies explained

• Chip-design software. These companies do not actually have silicon chip products of their own. Instead they sell electronic design automation (EDA) software tools, which help semiconductor companies configure new chip products more quickly. The global leaders in the field include US firms such as Cadence and Synopsis.

• Raw materials. One example here is AIM-quoted IQE which prepares the discs, or wafers, from which chips are manufactured. In IQE’s case, it provides specialist epitaxial wafers made of gallium arsenide (GaAs), gallium nitride (GaN) and indium phosphide (InP) which are used in specific markers such as markets such as mobile telecommunications and networking, rather than classic, mainstream pure silicon wafers.

• Fabless & chipless. Cambridge-based ARM is the daddy here, but this is how Alphawave IP operates, too. It does not make chips does not even have a chip design. Instead Alphawave IP licenses out an idea, or architecture, which chip companies can then use as the basis for their own designs and products and all three are therefore known as semiconductor intellectual property ('Semi IP') companies. The firm earns license fees and also bags a royalty fee for each chip sold which is based on their architecture. This business model can be tremendously profit and cash generative, especially once royalty volumes reach a certain scale, as those revenues drop straight through to the bottom line. ARM was acquired by Japan’s Softbank in 2017 and is now the subject of a bid from America’s NVIDIA. Imagination Technologies was another example of a UK-based Semi IP firm. It was acquired in 2017 by Canyon Bridge, albeit only after its IP architectures were dropped by Apple, a major customer, so this operating model is by no means totally impervious to shocks, even if it does help to shelter players in this field from the worst of swings in the wider semiconductor industry cycle.

• Fabless. CML Microsystems designs and sells its own products, but it does not make them (and this was also the case with Wolfson and CSR, formerly UK-listed firms that were ultimately acquired). The manufacturing process is outsourced to a so-called silicon chip foundry (an area where Taiwan dominates, via TSMC and UMC, both of which are quoted on the Taipei stock exchange and have secondary listings in the USA). Fabless companies receive their income in the form of royalties, which are generated when a product featuring one of their chip designs is manufactured and sold. This model is very profitable if end volumes are strong but can run into problems when chip manufacturing capacity is tight, as the subcontractors can charge more for the manufacturing process, eating into the fabless firms' profits.

• Integrated. These firms design, sell and also manufacture their own chips. They are therefore highly operationally geared and will make extremely high margins when its factories are fully utilised, but can quickly plunge into loss if demand starts to waver and the production lines are not kept very busy. There are no real examples of this left on the UK market, but world leaders in this sphere include American microprocessor giant Intel Franco-Italian combine STMicroelectronics, Germany’s Infineon and Korean tech behemoth Samsung Electronics, whose prowess in the field of memory chips is unquestionable.

• Chip-making equipment. Chipmakers need to pack their factories with so-called semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SPE), kit which is used in the multi-stage process of manufacturing their products. When the semiconductor cycle is strong, chipmakers will build more factories, and order more equipment, to help them meet demand, but in a downturn, capital expenditure budgets are pared back to the minimum and orders postponed or cancelled. The UK is a bit bereft of listed pure SPE plays although precision instrument experts Spectris, Renishaw and Gooch & Housego are sub-suppliers of key components to SPE companies, where global leaders include the Netherlands' ASM Lithography, America's Applied Materials, LAM Research and KLA-Tencor, as well as Japan's Tokyo Electron and Advantest.