“A call from Democratic Party senators Chuck Schumer and Bernie Sanders to rein in corporate share buybacks, subject to certain conditions, will please those who worry about excessive financialisation within the economy and enrage those who believe the companies and free markets are the best allocators of capital, not Government,” says Russ Mould, AJ Bell investment director. “The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle. But investors should perhaps bear in mind that share buybacks in America were only effectively legalised by the Securities and Exchange Commission’s rule 10b-18 during Ronald Reagan’s pro-markets Presidency in 1982, having previously been outlawed as a form of share price manipulation under the 1934 Securities Exchange Act.

“Senators Sanders and Schumer are concerned about record levels of buyback activity in the USA in the wake of President Trump’s 2017 corporation tax cuts. Their argument is that firms are lavishing capital upon buybacks at the same time as they lay off staff and restrain capital investment, when the Trump tax plan was designed to stimulate hiring and spending rather than financial engineering.

“We are still awaiting the final tally of buyback spending in 2018, as the final fourth-quarter results come in from US quoted companies. But US firms spent a record $204 billion on buybacks in the third quarter of last year and $583 billion in the first nine months, up 58% and 53% year-on-year respectively.

Source: Standard & Poor’s

The case for buybacks

“Despite the senators’ concerns, investors will argue that there are four clear arguments in favour of share buybacks.

• If a company is generating surplus cash it can return it to shareholders and let them decide what to do with it, rather than splurge it on an unnecessary acquisition or capacity increases. This is a particularly acute issue at the moment when low interest rates mean firms are not gaining a decent return on any cash holdings.

• Buybacks can work for individuals depending on their tax situation, and whether they prefer to be taxed on a capital gain (buyback) or dividend (income).

• Anyone who elects to retain their shares when a firm buys back stock will have an enhanced stake in the company and thus be entitled to a bigger share of future dividends (assuming there are any).

• They can also suggest that a management team feels a company’s shares are undervalued, so any move to buy back stock can be seen as a vote of confidence in the firm’s near and long-term trading prospects.

Reasons to be cautious on buybacks

“It is understandable how buybacks can be seen as perverse at firms that are cutting staff yet rewarding shareholders with what is deemed as ‘surplus cash’ at the same time.

“Wal-Mart, Harley Davidson and Wells Fargo are all examples of this in 2018 and even from the narrow perspective of portfolio construction there are four reasons to treat share buybacks with some degree of caution and not blindly welcome them all as a good thing.

• History shows companies have a habit of buying stock back during bull markets (when their stocks tends to be more expensive) and not doing so during bear ones (when their stock tends to be much cheaper). For example, buybacks in the US topped out in 2007 and collapsed in 2008 and 2009 only to reach new highs in 2018 as stock prices reached new peaks.

• This in turn exposes investors to the risk management teams are buying high rather than low could therefore question whether executives are sufficiently objective when they sanction a buyback to show the market they feel their stock is undervalued.

• A buyback could be used to massage earnings per share figures by reducing the share count at limited cost. This could be used to trigger management bonuses or stock options.

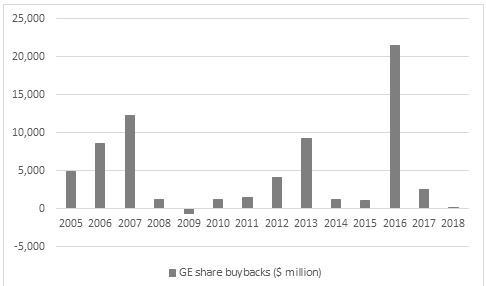

• There is also the risk that firms buyback stock using debt, potentially weakening their balance sheets and competitive position in the long term (although the same danger lurks with dividends). General Electric, which has spent more than $40 billion on share buybacks since the end of the Great Financial Crisis, is a horrible example of this. The debt taken on board to fund buybacks, as well as acquisitions, has weakened the company and left it struggling to invest in its competitive proposition to customers. As profits have turned down the borrowings have become a crushing burden that has forced new management to sell assets and prompted the shares to collapse.

Source: Company accounts

Source: Refinitiv data

“Bearing this in mind, investors must therefore look at how a company buys back its stock.

• If it does so in a disciplined manner, clearly setting a maximum price that it is prepared to pay (and explaining why) then the buyback could help to create shareholder value through the efficient deployment of cash.

• But if a company buys shares at any price then its buyback programme should be treated with scepticism. Such indiscipline would raise suspicions that management is simply trying to massage the share price or earnings targets or both, especially in managers are using cheap debt as a source of funding rather than internally generated cash.”