Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

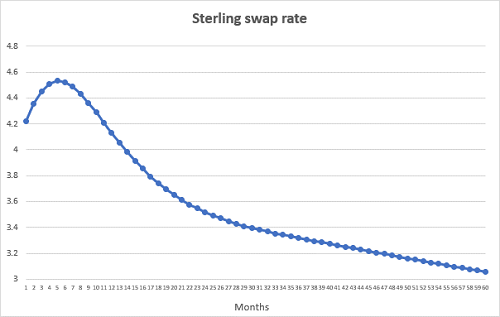

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) thinks that interest rates will soon be heading back towards pre-pandemic levels, and the market agrees. In the US, the market is pricing in interest rates being around 0.5% lower by the end of the year, a shift in sentiment precipitated by turmoil in the banking sector. In the UK, markets think there might still be an extra pump in the tightening cycle in the coming months, but are still forecasting interest rates to fall back in the longer term. The chart below shows the overnight sterling swap rate over various time horizons in the next five years, which gives an indication of expectations for base rate.

Source: Bank of England

It’s important to recognise that the IMF is suggesting interest rates will head back towards pre-pandemic levels, not that there will be a wholesale return to zero interest rate policy. Their analysis suggests that in the UK the natural rate of interest is around 0.5% above inflation, which would mean a nominal interest rate of 2.5% assuming the central bank can hit its inflation target. Even then, the IMF concedes that there is a considerable range of possible outcomes around this baseline scenario, and there are a lot of economic projections which serve as inputs to the model, and which themselves could be wide of the mark. In other words, the IMF’s findings have a wide margin of error and should be treated with caution.

It’s difficult to see how interest rates could be cut when CPI still stands at around 10%, but inflation is forecast to recede rapidly over the next year, with the latest report from the Bank of England suggesting that it will fall to 1% in 2025, and just 0.4% in 2026. That gives some credence to the IMF’s claims, and also implies that current expectations of monetary policy are too tight. Clearly economic projections need to be taken with a healthy dose of salt, especially when febrile commodity markets and fractious geopolitical conditions heighten uncertainty. However, history tells us the flatlining base rate between 2009 and 2022 was an aberration, and that interest rates move in cycles of rising and falling. Investors should therefore give some thought to what lower interest rates might mean for markets, as there will inevitably come a point when central banks take their foot off the brakes and shift it across to the accelerator again.

Falling interest rates should be good for share prices, because this boosts valuations and makes debt more manageable. Lower rates would be especially good for growth stocks with more distant earnings streams. These are precisely the kind of stocks that have sold off most heavily as interest rates have risen, reducing the value of future cashflows. Investors might not find they have to pivot too hard back to growth companies however. While falling share prices over the last year will have reduced the weighting of these funds and shares in a portfolio, they have performed so well over the last five and ten years investors may find they already have quite a lot of exposure to this area. Having a balance between growth and value strategies within a portfolio means you won’t be up the creek without a paddle should inflation prove sticky, forcing interest rates to remain high.

Bonds also stand to prosper in a falling interest rate environment, which would be a reversal of fortunes from the last twelve months. That would help to bolster the value of more conservative funds that have high exposure to fixed interest securities. We could also expect annuity rates to fall back again, as these are mainly backed by bonds bought by insurance companies. Lower bond yields would also likely increase demand for other comparable assets that are used as safe havens or for income, such as gold, commercial property and infrastructure.

House prices would also stand to benefit from lower interest rates as mortgages would become cheaper, and that by extension would be good for housebuilding stocks. On the flip side, cash rates would fall back and savers would be left with fleeting memories of their moment in the sun. If the IMF is on the money and the natural rate of interest in the UK is around 0.5% above inflation, that doesn’t bode well for savers getting a particularly handsome real return on cash in the bank over the long term.

It seems unlikely that when interest rates start to fall back they will do so as sharply as they have risen, barring some form of economic crisis. However, markets will start to adjust to the new interest rate environment in advance and the resurgence we have seen in the global stocks this year is already a sign of shifting expectations for monetary policy. But there’s no such thing as a one way bet in markets, so investors would do well to make sure they have a mix of assets and strategies with opposing interest rate sensitivities. That should help their portfolio make ground in both falling and rising interest rate environments.

These articles are for information purposes only and are not a personal recommendation or advice.

Related content

- Thu, 16/05/2024 - 14:40

- Tue, 14/05/2024 - 14:39

- Fri, 10/05/2024 - 09:39

- Fri, 10/05/2024 - 09:27

- Thu, 09/05/2024 - 16:17