Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

A five-point plan for emerging markets

The definition of an emerging market has often (jokingly) been a market from which you cannot emerge fast enough when it all goes wrong.

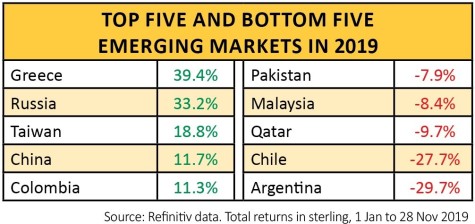

Argentina and Chile are 2019’s examples that seem to support this rule as the former lurched into its latest debt crisis and the latter into a fresh political one, but overall there was no need to rush for the exits.

All of the major regions as a whole – Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America and the Middle East – have generated positive total returns in sterling for the year. Eastern Europe ranks second out of the eight major geographic options available to investors, buoyed by a strong performance from Russia in particular.

However, emerging markets have still generally lagged developed ones this year. This continues a trend that has been evident for most of the decade. Emerging markets have simply failed to compensate investors for the political and economic risk they have taken. Portfolio builders would instead have been better served by playing it safe and keeping their money in developed arenas such as Western Europe, Japan and the US.

Five rules

A deeper look at the performance of emerging markets shows five clear themes.

1. Economic growth does not guarantee strong equity market performance

A good example is China which lurks seventh from bottom in the list of EM nations with a total return in sterling of just 7%, despite a decade of large GDP increases.

2. Quality of economic growth is important

Greece boomed in the 1990s and early 2000s but its progress was based on borrowing that proved unsustainable.

Turkey has blown similarly hot and cold thanks to its reliance on borrowing and a current account deficit. Both finally hit the buffers.

India, by contrast, has relatively low sovereign debt, as do Thailand and the Philippines, which both learned about debt, and especially the dangers of borrowing in overseas currencies, during the 1997-98 Asian crisis. They have taken those lessons to heart, lessons which the West now seems keen to ignore.

3. Currencies and the dollar matter

This takes us back to economic fundamentals. Brazil’s BOVESPA index stands nears its all-time highs at 110,000 but the real has gone from BRL 3.0 to nearly BRL 5.45. Devaluations in Turkey and Egypt have also hurt returns.

The last 20 years show that a strong dollar is generally bad for emerging markets and this takes investors back to the issue of debt.

Many emerging markets borrow dollars so when the buck rises that makes paying the interest more expensive in local currency terms. Argentina has effectively defaulted again, while Turkey frightened many overseas lenders in 2018.

A weak dollar would buy a lot of EMs breathing space, although that probably needs the US economy to weaken and lose its lustre, perhaps weighed down by its own monstrous budget deficit.

4. Politics matters

Investors are more likely to look favourably upon markets that are going from left to right (as per Greece this year and Brazil since 2018) than the other way (Argentina being a glaring example).

In markets where authoritarian figures are in charge – such as Russia – investors, if they think valuations justify the risks, are better off siding with government-backed firms than their rivals.

5. Commodities matter

This is often dismissed by EM specialists as lazy shorthand and frankly it may well be, especially as some EMs are net exporters and others net importers. But overall, the historic relationship between the Bloomberg Commodity index and the MSCI EM index seems clear.

The final chart may be the most telling. This decade can be characterised by low growth, low interest rates and soggy commodity prices. The US has been the best place to be, as it is packed with technology companies with strong secular growth and home to the deepest, most liquid markets and the world’s reserve currency. Maybe EMs need a return to cyclical growth and inflation to really shine again.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Exchange-Traded Funds

Great Ideas

Great Ideas Update

News

- Japan’s public pension fund bans short-selling on ESG grounds

- Black Friday boost for retailers including Boohoo

- Good and bad: how the Tories and Labour could impact your wealth

- Investors ‘may only see small UK market bounce’ on a Tory majority win

- Activist investor accuses mainstream managers of ‘greenwash’

- What are the prospects for oil prices and big oil firms?

magazine

magazine